Laméca file

Cuban Abakuá music

3. ABAKUÁ CEREMONIAL MUSIC

Abakuá music is ceremonial. Each step of an Abakuá ceremony - whether an initiation or a funeral - is accompanied by music, consisting of chants by a lead voice and chorus performed either a cappella, or to the accompaniment of a percussion ensemble (with drums, rattles, and a metal bell). Other facets of Abakuá ceremony are accompanied by ritual sounds: a symbolic drum called ‘Mpegó’ is hit four times to call the group to order (1); an iron bell called ‘Ekón’ is hit with a stick in order to communicate with ‘Ékue’ - the mystic Voice of the leopard - in the sacred forest in order to evoke its presence inside the temple; the resonant sound of the mystic Voice authorizes the ceremonial process of initiations and funerals; the metal bells worn around the waists of the ‘Íreme’ body-maskers are shaken to frighten-off negative spirits in the ceremonial space; a title-holder called Moruá Yuánsa shakes ‘Erikúnde’ rattles in his hands in order to communicate with and guide the Íremes into action.

The metal bells around the waist of the Íreme are used to scare away negative spirits. Bario ‘la cuevita’, San Miguel de Padrón, Havana, 2013.

Photo : I. Miller

The “Moruá Yuánsa” title-holder of an Abakuá lodge guides the Íreme mask with an eight-point ‘erikúnde’ rattle. Barrio ‘la cuevita’, San Miguel de Padrón, Havana, 2013.

Photo : I. Miller

The “Moruá Yuánsa” title-holder of an Abakuá lodge guides the Íreme mask with an eight-point ‘erikúnde’ rattle. Barrio ‘la cuevita’, San Miguel de Padrón, Havana, 2013.

Photo : I. Miller

Efik Ékpè display at the University of Ibadan. Member at right shakes rattles to guide the Ékpè mask. Calabar highlife musician-composer Chief Inyang Henshaw stands between them in back.

Photo : Jean Borgatti, 1974

Painting at an Ékpè hall in Ohafia, representing a member (at left) guiding an Ékpè mask with a rattle in each hand.

Photo : I. Miller, 2011, 2012

Sculptures at an Ékpè hall in Ohafia, representing a member guiding an Ékpè mask with a rattle in each hand.

Photo : I. Miller, 2011, 2012

Abakuá chants are performed in a language based upon that brought to Cuba by the African founders of the institution in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (cf. Cabrera 1988). The language is taught only to members, and is therefore ‘secret’. The words are thought to have a spiritual power able to activate the latent potential in objects, animals and humans. When performed correctly they are believed to evoke the presence of the spirits of the founding ancestors of the institution in West Africa centuries ago. Originally in Africa, Abakuá (i.e., Ékpè) had 13 original titles, while many more were created later. Each title has its own mythology and series of titles; so too each ritual object, including the musical instruments, all of which are evoked through chanting to the accompaniment of music during the ceremonial process. With this complexity, there are many variations of Abakuá ceremonies depending on the initiation or funerary rites of any one of the titles, not to mention those of the regular members. In its totality, the ceremonial process tells the story of the foundation of Abakuá in Africa.

Abakuá ceremonies begin when the title-holders gather inside the Fambá (temple) to cleanse the space through complex rituals that last for several hours. Once the space is purified and otherwise prepared, the titleholders Ekuenyón and Mpegó exit the Fambá. Ekuenyón with his drum, called Kankómo Ará risún (‘the drum of the face of Ekue’), and Mpegó, with an Ekón (metal bell) and a short stick. They begin the process called ‘rompimiento’ (‘breaking’ or commencement) by chanting on the patio, which is considered the ‘sacred’ forest because of the special trees planted there.

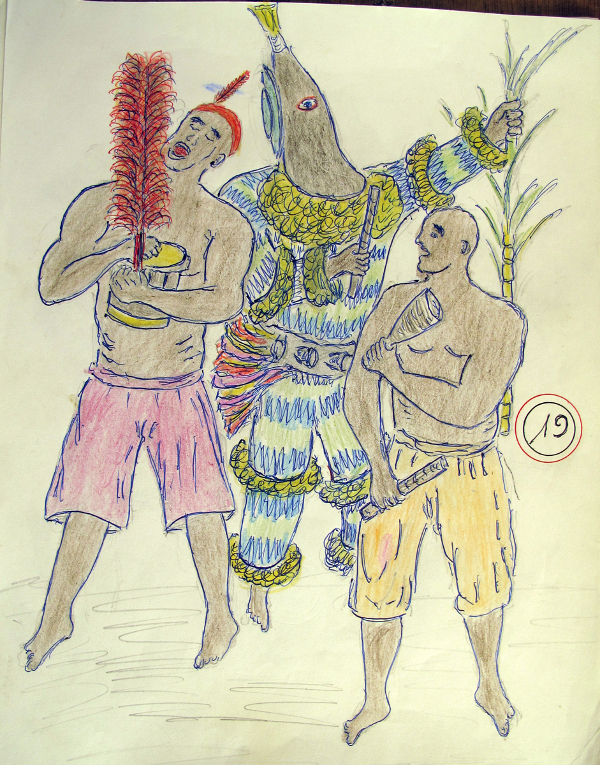

“Rompimiento.” Ekuenyón with drum, Mpegó with metal gong, and Íreme Mbóko with cane stalk.

Reinaldo Brito del Valle drawing, 2013

Ekuenyón begins to tap his drum while Mpegó hits the Ekón with a stick, in order to evoke the ‘mystic Voice’ of Ékue that will authorize the initiations.

"Abakuá - Ekuenyón" (extract) by Victor Herrera, from Viejos cantos afrocubanos: antología de la música afrocubana. vol. 1 (EGREM, 1962).

Normally only one Ekuenyón and one Mpegó search for the Voice. This recording has the voices of two alternating Ekuenyóns, each carrying their own drum, each accompanied by a different Mpego with their own ekón. This would occur in the rare case of two lodges ‘planting’, each Ekuenyón and Mpegó working with the Fundament of their particular lodge.

When Ekuenyón is searching for the Voice, he also mentions all the musical instruments used in Abakuá rites.

The ekón (metal bell) is a symbol of Abakuá itself, because it communicates with the ‘mystic Voice’. In the Abakuá origin myth, the ekón was used when seeking the Voice for the first time in Usagaré (a community near Calabar). The ekón marks time in the percussion ensemble, and also transmits sounds to the mystic Voice that enable the spiritual functions of Abakuá rites.

The ekón guides all the actions of Abakuá ceremonies, whether initiations or funerary rites. The ekón has many titles. One of them is, “Ékue munansénde, Ékue munansénde, ekón nkríbia ekón ndibó”; this title speaks to the first time the ekón was used to find the Voice in Africa. In both Cuba and Africa, ekón is the only instrument that is marked with chalk in the same way that initiates are marked (2).

The nkong ‘metal gong’ in Ékpè practice in Calabar. The gong, marked with red and white chalk, sits on the plantain-leaf covered ‘high-table’ of the chiefs. Efe Ékpè Efut Ifako, 2010.

Photo : I. Miller (thanks to ‘Ndabo’ Etim Ika)

The nkong ‘metal gong’ in Ékpè practice in Calabar. A neophyte is marked in red and white chalk. Efe Ékpè Efut Ifako, 2010.

Photo : I. Miller (thanks to ‘Ndabo’ Etim Ika)

The nkong ‘metal gong’ in Ékpè practice in Calabar. At Efut Ekondo Landing, Calabar South, Chief Ironbar (with gong) and Muri Edem (with cap), evoke the gods of the water and land at this disembarking point of Efut Ekondo migrants from Cameroon into Calabar centuries ago.

Photo : I. Miller, 2008

The nkong ‘metal gong’ in Ékpè practice in Calabar. As the ‘mystic Voice’ resounds at the Efe Ékpè Iboku, Atakpa community, Calabar, a member uses the gong to communicate with it.

(In Cuban Abakuá practice, when the ekón ‘gong’ communicates with the Voice, its mouth is positioned upwards to ‘play for the heavens’, as in this photograph).

Photo : I. Miller, 2011

The nkong ‘metal gong’ in Ékpè practice in Calabar. After the Ékpè session is commenced by the chiefs proclaiming their status while sounding the gong at the ‘hightable’, the gong is used by the musicians to play music. Efe Ékpè Efut Ifako, 2010.

(In Cuban Abakuá practice, when the ekón ‘gong’ is used to play music, its mouth is

positioned downwards to ‘play for the ancestors’).

Photo : I. Miller, 2010

Once the Ekón evokes the ‘mystic Voice’ of Ékue inside the temple, the title-holders prepare to exit in a procession to greet the stars and planets.

The first act of Abakuá music occurs with the procession that exits the Fambá ‘temple’ after the mystic Voice sounds. Before 1959 this occurred at 12 midnight, but after 1977, the authorities began to give permissions for the procession to leave at 6 a.m. These days (2013), authorities are giving some permissions for the processions to leave at 12 midnight, as in the past.

Abakuá ceremonies are organized according to the position of the planet earth in relation to the stars. The procession at 12 midnight greets the stars, while that in the early morning greets the rising sun.

In the 1950s, Lydia Cabrera wrote:

“At twelve in the night, when the plante ‘breaks’ [i.e., the Voice resounds]... the officiants leave in procession... each dignitary marches carrying their corresponding attributes and drums” (1954: 216). (3)

As the first procession leaves the Fambá, the members chant in reverence to Mokóngo, one of their leading titles :

“Eribo Mokóngo machébere, Ékue Ékue, chabiáka Mokongo machébere, Ékue Ékue.” [repeat]

This chant tells an allegory of the title-holder named Mokóngo, who was the ‘king’ of his tribe in Africa, as well as a leading intellect, because he directs the ceremonial process. Mokóngo leads the procession.

During this procession they also chant :

“Abasí berómo, ebión endáyo.” [2x]

This chant expresses respect to the sun and to the stars that are blessing the ceremony.

They chant :

“Eribó anangandó, yayo Moruá yéne gúbia.”

‘the Eribó (drum) goes to the river; greetings to the Voice brought by the woman’ (Sikán).

This chant is a reverence to the Eribó drum that presides in the procession.

"Eribo anangando".

When returning to the Fambá temple, those in the procession chant :

“El Eribó, el Eribó, el Eribó, sanga baróko fambá.”

‘The Eribó is entering the Fambá’.

The Eribó is a symbolic drum that is not played.

Equidistant along its rim stands plumed rods, usually four in number, that represent the four kings who founded Abakuá in the mythic past.

“Eribó Sése Moguimban.” Drawing from an Abakuá manuscript.

Photo : I. Miller

Display of the Murua-Nyamkpe chanter, at the palace of the Obong of Calabar.

Compare the plumed rods on the Cuban Eribó and on the head-piece of the Calabar Murua dancer. Both have a center plume surrounded by others with feathers that flow out at the top. In Calabar, these are called ‘uduok mbara’ or ‘falling dew’.

Photo : I. Miller, 2010

Outside on the patio, the musicians continue playing, and one of the Moruás (lead chanters) asks, “Which lodge is ‘planting’ ? (having a ceremony), with this phrase :

“Awanalória awanalória Abakuá.”

Another Moruá in the gathering responds, for example, if the lodge Efóri Kómo is ‘planted’: “Efóri Kómo, íbio kóko naróbia.”

With this phrase, all gathered know that Efóri Kómo is ‘planting’.

Abakuá procession entering the Efori Komo lodge. Barrio “Los Pocitos”, Marianao, Havana, 2002.

Photo : I. Miller, 2002

As expressed in the chanted phrases, and as symbolized in the mythic-histories of the instruments, the music represents all that is done in Abakuá ceremonies.

The names of three drums used for music are evoked in this chant : “Obi ápa, Eró apá, Kuchíyeremá.” The ekón ‘bell’ starts the music. The Obi ápa drum is called number one because it is the first drum to play (i.e., ‘el salidor’); it is given two hits to each measure. The Eró apá drum is called number two because it is played after the Obi ápa; it is given three hits to each measure. The Kuchíyeremá drum is number three; it is given one hit to each measure. The Bonkó is called the ‘repicador’ (that which ‘rings out’) because it spontaneously communicates with the dancers.

Abakuá percussion ensemble (three drums and a metal gong) plays in the “válla” on the patio of an Abakuá lodge during initiations.

Photo : I. Miller, 2013

Abakuá percussion ensemble (three drums and a metal gong) plays in the “válla” on

the patio of an Abakuá lodge during initiations.

Photo : I. Miller, 2013

Abakuá music is played similarly in the cities of Havana and Matanzas, with the distinction that the Eró apá drum (i.e., the ‘three hits’); is played one way in Matanzas, and another in Havana. The Obi ápa ‘salidor’ is played the same in both cities.

"Marcha Efi de La Habana : Ekon y Enkomo Kuchi-Yeremá".

"Marcha Efi de Matanzas : Ekon y Enkomo Kuchi-Yeremá".

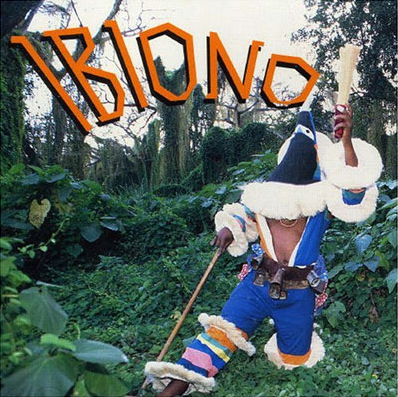

The Abakuá term for music is Ibiono. Ibiono is ‘proper music’, ‘perfect music’, or ‘music with swing’. (4)

In addition, Ibiono can refer to the human voice while chanting, as well as to the Voice of Ékue. One of the phrases for Ibiono is : Ibióno untererán, wána mutéke aná mendó, Ibiono untererán ! (5)

When the “válla” begins, the Moruá chants the names of the musical instruments. To evoke the Abakuá musical instruments, they chant :

“Biankomo, biankomo, biankomo eee.

Biankoméko awána kasína mendó.

Yuánsa Biankoméko, Awana Bekura Mendó,

Asére Bonkó Enchemiyá eeee.

Ekón kríbia ekón anamendó.”

The last phrase means, ‘the ekón comes from Awana Bekura Mendó’.

"Marcha Efí de la Habana" from Antologia de la musica afrocubana, vol. 10 Abakuá (Areito), Goyo Hernández (lead).

The beginning phrases evoke Abakuá musical instruments.

The Bonkó is considered a ‘talking’ drum that has both musical and ritual functions. It is played by the titleholder called Moní Bonkó. Here are some phrases used to chant for the Bonkó drum :

“Ékue tária bonkó, Ékue tária bonkó. Afón eriero bonkó,

afón eriero bonkó. Omeriero bonkó, afón eriero bonkó.

Ékue nyangué, Ékue bonkó.”

“Apapá nyímiyá, Bonkó enchemiyá.”

"Apapa Efí" from Ibiono (Caribe Production, 2001), Ángel Guerrero-Vecino (lead voice), Pedro-Suárez ‘El Yuma’ (prayer to the Bonkó drum).

This recording has phrases from the mythic-legend of the Bonkó, with reference to the war between the Enyémiyá and the Ekerewá to take possession of the ‘bakarióngo’ cloth and to consecrate the Bonkó in Efí land (i.e., Apapa Obane).

In the “válla” they ask :

“Itá bonkó íro, nyenisón Obáne?”

‘what was the first voice of Obáne?’

The response is :

“Ékue tária bonkó, akanarán Obáne.”

‘The bonkó was the first Mother of Efí.’“Sankóbio abanékue etéte Ékue Efí?’

‘which was the first abanékue of Efí?’

“Ékue tária Bonkó.”

If the lodge ‘planting’ is from Orú territory (i.e., an Orú lineage), they chant :

“Biankoméko awána Sése Orú.” (6)

‘the music from Orú territory.’

"Oru Afiana" from Ibiono (Caribe Production, 2001), “Pablito”, Moruá Yuánsa de Bakokó Efó, lead voice.

In the past, it was common that Abakuá members would invite the women in their families to ‘plantes’. From their seats on the side-lines of the patio, they would join in the chorus of Abakuá music in the “válla.” This tradition continues today in the barrio of “Los Pocitos” on the outskirts of Havana. (7)

"Encame de Abakuá (Efó-Efí)" by Conjunto de percusion de danza nacional de Cuba, Homenaje: Jesús Pérez in Memoriam (Areito, 1987).

Women are heard in the chorus of this track.

During a baróko (a ceremony to initiate title-holders), those in the válla (circle of musicians on the patio) chant phrases related to each ritual sequence that occurs in the ceremony. The Moruás chant the stories for each of the titles being consecrated. As the mbóri (goat) is sacrificed, they chant the legends of the goat in Africa. In this ceremony, Moruá Yuánsa (a title that directs the chanting) must chant phrases of authorization that allow Mpegó to draw the signs of authorization on the earth, trees and ritual objects. As Moruá Yuánsa prays, the drums are silent. Then, as Mpegó draws the signs, the drums play as Moruá Yuánsa chants phrases for each of the signs being drawn.

For the signs, they chant :

“Ya yo eee, ya yo ma eeee, awa beró akanawán Moruá tánboribó Iyámba, ya yo eee, ya yo ma eeee.

Ngomo ngomo ngomo aaa, ngomo ngomo ngomo eee...

Yuánsa seré, yuánsa naróko [2x],

Ngomo anábia koko mbára chitubé, ooo Ékue, aberitan inóko. aberitan inóko, aberitán obé [2x].

Once the signs are drawn, they are sprayed with cane liquor while chanting :

“Mimba, mimba, mimba.”

Next they are sprayed with dry wine while chanting :

“okoró besuá eee.

Then they are sprayed with ‘holy water’ while chanting :

“Sánga nini sánga nin...

[also] umón anyó bibí, enyén irén kamároró.”

In this context, the ‘holy water’ is not from the church !

It is water that Nasakó brought it from the river, and blessed by Isué. It represents the mythic water in Africa taken from the spring called Kamaroró in Usagaré.

Next a ceramic tile holding burning incense is used to blow smoke over the signs, while chanting :

“sámio, sámio, sámio.”

At this point, all is prepared for the sacrifice of the goat.

During the ceremony of the sacrificial goat, the members chant :

“ya yo ee, ya yo ma eee [2x]

awa beró akanawan Moruá tan boribó Iyámba, ya yo eeee, ya yo ma eeee. Ákua mpána ooo, ákua mpána.

Ákua mbori oo, ákua mbóri ooo, Ékue Iyámba.

Eeeee, ákua mbori aborokí nyangué aberenyán tantan

Aberisún tan koneyó, Aberisún mbóri, Aberinyán tan kuneyó eee.

Chékeréke longorí semó eee, chekeréke longori mayé, nandeee, nandeee, mbori nandee...” (the goat is killed).

Aberisún and Aberinyán are the titles of the Íremes who perform in the act of killing the goat. While the goat is killed, they chant :

“ákua mbori aborokí nyángué.”

"Canto Abakuá" from La música del pueblo Cubano vol. 1-2 (Caribe Production, 1987).

In ceremonies, this track is performed with drums.

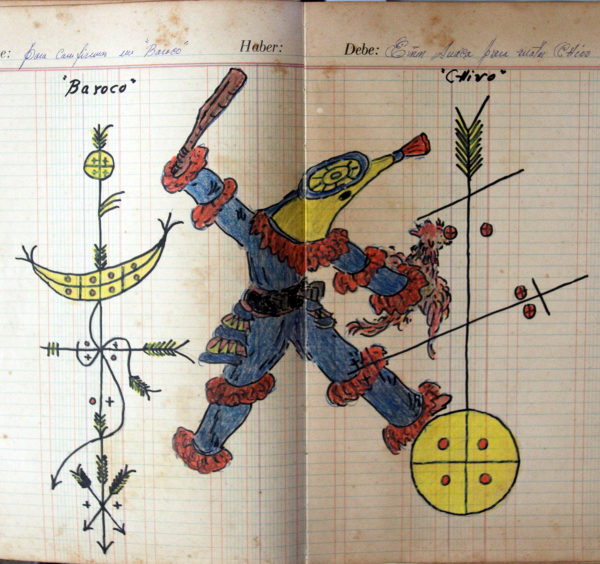

Abakuá manuscript with signs and Íreme for the goat sacrifice.

Photo : I. Miller

Goat prepared for sacrifice in Efut Ekondo, Calabar South, during the annual cleansing rites of the Lodge.

Photo : I. Miller, december 2007

As they remove the head from the goat, they chant :

“chéne chéne ákua chéne, chéne chéne ákua nyogó [3x].

Iyámba motangué Ékuenyón nyánga riké.

Ekuenyón carries the decapitated goat head inside the temple in a procession with all the title-holders, while the music continues in the “válla” on the patio.

While entering the Fambá with the head, they chant :

“Sikánékue minuá ngo boróko tínde.”

This is a reverence to the woman.

Later, Isué and all the title-holders carry ritual objects, accompanied by the Íremes, to exit the temple in order to gather the goat skin. They remove the skin from the goat’s body while chanting :

“Baróko nandibá naróko.”

In order to collect the skin, Isué must recite a prayer while all the others are silent. Then while gathering the skin, all chant to the accompaniment of drums :

“Amana ko íba [2x], nyóngo iró sése, manyón kení ngomo, bongó erú efó.”

Next all the title-holders prepare to enter the Fambá, while they chant :

“Baróko, nandibá baróko [4x],

amako enyéne kanimá,

sangá baróko fambá [2x]

All the title-holders enter the Fambá to perform the baróko inside. When the baróko is finished, the musicians in the ‘valla’ chant the following to prepare for the procession :

“Eribó maka maka, Eribó, eribó maka térere. Bario ! Eribo maka, Isué eribó, eribó maka térere. [2x]

"Abakwa song" from Cult Music of Cuba (Folkways Records, 1951).

Recorded by Harold Courlander (Guanabacoa, Cuba, 1940s).

Then all leave the Famba in a procession with the Eribó drum and all the ritual objects along with the Íremes. Íreme Nkóboro guides the procession; when Nkóboro puts his feet outside the Fambá, all chant the same phrase as used in the first procession :

“Eribó Mokóngo machébere, Ékue Ékue, chabiáka Mokóngo machébere, Ékue Ékue!“

As the procession moves outside, the members chant to the glory of the titles that were consecrated, beginning with the most prominent and then the others.

Abakuá procession through the barrio of “Los Pocitos”, Marianao, Betóngo Naróko Efó Lodge, Havana.

Photo : I. Miller, 2002

The baróko is now complete. If there are neophytes to swear-in as new members, the preparations to initiate them as ‘abanékues’ (ordinary members) begin at this point.

This ceremony begins with a chant for the herbs and other ingredients used to magically evoke the founding spirits of the Abakuá :

“Wémba wémba wémba !” oyo oyo oyo

"Wemba" by Victor Herrera, from Afro-Cuba: A Musical Anthology (Rounder Records, 1994).

During this chant, ritual cleansings are performed with herbs and a rooster.

The title-holders begin to draw signs in yellow chalk on the neophytes, and all chant :

“Ngómo ngómo ngómo... ” (the chalk).

“Apotácho Moruá Eribó, Mpegó elorí butáme [2x].

“Mpegó ana muto ngómo.” [2x]

The neophytes are sprayed with distilled cane liquor, and all chant :

“Mimba, mimba, mimba.”

Next the neophytes are sprayed with dry wine, and all chant :

“Mimba akanansé okoró besuá eee.

Next the neophytes are sprayed with ‘holy water’, and all chant :

“Sánga nini sánga nini...”

Next they blow incense smoke over the bodies of the neophytes while chanting :

“sámio, sámio, sámio...”

Then as the Íreme Eribangandó arrives to ritually cleanse the neophytes, all chant to the new Obonékues :

“Enseniyén endíke, unparawáo, kénde ya yo ma,

Obonékue asére múmio, bóko etámbre.

enseniyén endíke, unparawáo, kende ya yo ma.”

As the Íreme Eribangandó cleanses their bodies with the rooster, all chant :

Nsdísime isún parawáo, kénde ya yo ma, kénde ya yo ma.

Nsdísime isún parawáo, kende ya yo ma, Eribangandó, kende ya yo ma.”

Each neophyte was sponsored by an Abakuá member (considered their ‘godfather’), who now stands behind the neophyte. After each blindfolded neophyte is cleansed, their sponsor leads them to the door of the Fambá, where the title-holders Isunékue and Mpegó are standing; Mpegó hold his (Mpegó) drum at hand. After Isunékue says a prayer, the neophyte is made to spin around thrice, then Mpegó hits his drum once to authorize the entrance of the neophyte, who is introduced into the Fambá. Thus ends the public aspect of their initiation.

At this point the music on the patio continues, now spontaneously with chants to the various lodges whose members are participating in the ‘plante’, as well as to the ‘African treaties’, i.e., the general mythology of Abakuá’s foundation in Africa.

Once the title-holders inside the Fambá finish consecrating the Obonékues, they all leave in a procession. Each new initiate carries a ritual attribute in their hands. The same chant for all the processions is performed. This procession moves to the Ceiba tree, the palm tree and then to the river that are in the patio space, thus reenacting the path made by Sikán with Tánse in mythic Africa when she carried the Fish in her ceramic jar.

After this procession, the new initiates form a circle in the patio. Mpegó draws a sign for the ritual communion, reenacting that drawn for the first communion food in Awána Bekúra Mendó, in Africa. When Mpegó is drawing, all chant: “Ngómo, ngómo, ngómo” as before.

Next a title-holder sprays the sign first with hard liquor, then with dry wine, ‘holy water’ and then blows incense smoke over it. When a lit candle is placed in front of the drawing, all begin to chant for the food :

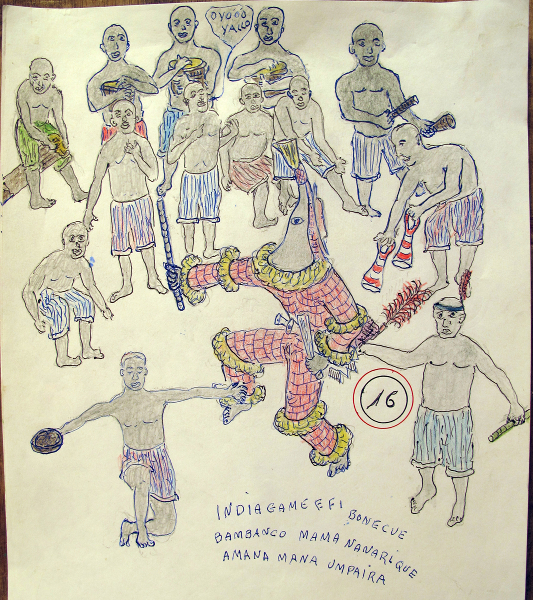

“Efí kínyóngo Obáne, Efí ke ndiagamé [2x], (the sign is called ‘ndiagamé’ or ‘plate’).

“Abakuá communion”; “Indiagame Efí obonekue bambanko mama nanarike amana

mana unpaira.”

Reinaldo Brito del Valle drawing, 2013

Next they chant :

Íria téte akáma ndéme Efí [2x]...

Íria awaranyóngo ekómbre [2x].

(‘the food offered in the forest’).

They chant :

“Batánga abarongá” (the name of the Mpegó who made the original sign of the food).

“Ítia manyéne kóndo eee.”

(A question: ‘who authorized the first food?’).

“Ékue amanantuáyo, Nkaníma amanantuáyo eee.”

(‘Ékue authorized it with the Íreme Nkaníma’).

At this point, the Nkríkamo arrives while beating his drum to guide the Íreme Nkaníma, while all chant :

“Úria, íria, ámia [2x], eririo unkére brándi masóngo.

Masonké masonké.”

This evokes both foods offered: that for the Fundament and that for the men. Ámia (short for ‘ámiabón’) was the

name of the fortress where the food for the Kings was given in Africa.

They chant :

“nyánya gobé” [3x],

“Nkaníma awaranyóngo” [3x].

“Íreme Nkaníma antrogofóko ama kwairén” [2x].

First, food offerings are given to Ékue while all chant :

“O yo yo yo, Ékue usagaré” [2x],

“irión ban bankó mamá nyanga riké,

irión ban bankó mamá eréniyó.”

Next, Nasakó lights a small portion of gunpowder that explodes, while one of the new initiates is directed to ‘steal’ food from the calabash-gourd placed in the center of the circle of initiates; he runs towards the forest while the Íreme chases him. The initiate always escapes, so the Íreme returns to the circle and begins to dance with the other initiates who begin to eat. Isué and the title-holder Nkandémo (the cook) share the food; all chant as the drums play :

“Amána mána unpáyra, obonékue unpáyra Amana mana unpáyra, iriámpo pijáwa.

Amana mana unpáyra, jeyey unpáyra.

Amana mana unpáyra...”

"Amana mana unpáyra".

Another chant :

“Indiagáme Efí,

Obonékue Indiagáme Efí” [2x].

After all eat, they chant :

“Yayo, ami ke kinyóngo.” [repeat]

‘I am Abakuá’ (i.e., I’m in a new category).

This is a creole (not an African) chant.

The ‘plante’ is now complete, although the initiates can continue their play until six in the evening before dispersing.

_________________________________

(1) Cabrera (1988: 362): “Mpegó: significa también silencio.”

(2) In one exception, in some Éjághám communities, the wooden gong (obodum in Efik) is sometimes marked with athe chalk during ceremonies.

(3) “A las doce de la noche, cuando "rompe" el plante, antes de la ceremonia oculta del juramento en el ekufón o fambá, salen en procesión los oficiantes... cada dignatario marcha llevando los atributos y tambores que le corresponde.” (Cabrera 1954: 216).

(4) Thanks to Robert Farris Thompson.

(5) In the Ibibio-speaking region of southeastern Nigeria, there is a community called Ibiono-Ibom, in Akwa Ibom State.

(7) Interview with Mercedes Fulgencia-Corps (2013) in her home in “Los Pocitos,” Reparto Marianao, La Habana. She is from an extended family where throughout the twentieth century, most of the men have been Abakuá members.

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. The Abakuá institution : a Carabalí foundation in Cuban society

2. Styles of Abakuá music : Nyánkue rites; Efó and Efí lineages; the lamellophone; percussion instruments

3. Abakuá ceremonial music

4. Abakuá influence in Cuban popular music

Musical examples

Glossary

Sources

______________________________________

By Dr Ivor L. Miller

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Départemental de la Guadeloupe, 2016