Dossier Laméca

VODOU MUSIC IN HAITI

5. Work and celebrate : konbit, carnival and rara

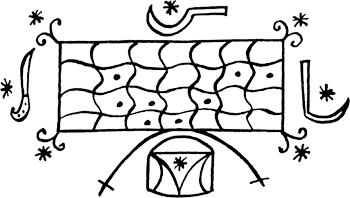

Vèvè for Azaka Mede.

Traditional Afro-Haitian music lives both in and out of the Vodou temple. Researchers, however, have oversimplified the classification of musical types in Haiti by distinguishing mutually exclusive sacred and secular activities. Just as we think of the Vodou pantheon as a continuum of spiritual energies, so we can place occasions that call for music and dance on a continuum of spiritual or material emphasis. Vodou music is most overtly spiritual because it calls the spirits, yet they enter the physical sphere and help the living with mundane problems. Beyond Vodou rites, the spirits dance in street festivals and agricultural work brigades, but an emphasis on public affairs and economic concerns attenuates their presence.

One finds cooperative work societies throughout rural Haiti. Some researchers have traced them to such models as the West African dokpwe, but others argue that they thrive wherever traditional modes of production persist. The most widely used name for the society, konbit, seems to derive from an archaic Spanish word meaning “to invite.” Inviting one’s neighbors to share a task requiring many hands—planting, weeding, harvesting, sorting—supports this theory.

The brigade includes a music ensemble. Musicians summon members, drive the rhythm of their work, and animate recreational breaks. A sanba or renn chantrèl (from the french reine chanterelle, melody queen) calls songs to the accompaniment of drums, bell (usually the blade of a hoe), and a variety of trumpets (described below). The lanbi, a conch trumpet, calls the workers just as it signaled militants during the Revolution.

The ensemble favors rhythms of the Rara dances (see below), djouba and kongo. At the party, or banbòch, that follows completion of the job, workers dance to kontredans (a version of the European contredanse, or quadrille) and the mereng peyizan (peasant meringue).

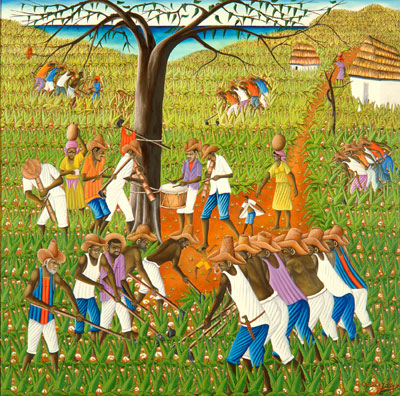

Gérard Valcin (Haitian, 1912-1988), Konbit (Communal Fieldworkers), 1971.

Oil on masonite, 44 x 43.75 in. Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Richard and Erna Flagg, M1987.27.

Haitian public revelry reaches its height with Carnival. Because its bands march from the first Sunday after Epiphany (January 6) to Mardi Gras (the day before Ash Wednesday), researchers often minimize Carnival’s African components. The French colonists did replicate the masked balls of Europe in the days before Ash Wednesday. Enslaved Africans in the cities took advantage of the work stoppage to animate urban plazas with their own festivities, to which they attracted Africans from the provinces. Proprietors regarded their style of revelry as a risky but necessary release. Following independence, traditional Haitian Carnival took on its present form: ambulant costumed bands, with members caricaturing kings and queens, Indians, Arabs, devils, and prominent citizens.

This faded photograph captures the Carnival revelries of young men from an impoverished Port-au-Prince community, circa 1967. We see the lead Petwo drum and a small Congo ka (also named kata after its rhythm) in the center of the group.

Each band has its musicians and dancers who perform maskawon, mazòn and such round dances as the stick dance, batonis. Long flared metal trumpets called klewon recall African wind ensembles and complement goatskin drums, tchatchas and scrapers called graj.

Against the backdrop of kata-driven music, Carnival songs express biting commentary and the risqué. The southern city of Jacmel presents the best traditional Carnival today, while Port-au-Prince has modernized the festival in recent years to feature commercial bands on trucks loaded with mega-speakers.

"Kontredans" (extract).

"Carnaval" (circa 1947) (extract).

"Potpourri" by Tallon rara band (1978) (extract).

Haitians weave sacred and profane, work and play in Rara, a public performance often seen as a rural Carnival. Rara bands cross the countryside on Sundays following Ash Wednesday, building up to an Easter Week festival. As with Carnival, timing with the Christian calendar dates back to the French period when colonial law granted the enslaved time off for Holy Week. Characters from the New Testament, Vodou, and the Amerindian past meet in the Rara drama. Work and play blur in pouring libations, dancing, “throwing” songs, cracking whips, and beating drums. As in Carnival, Rara musicians use the goatskin drums of Kongo/Petwo rites, the tchatcha, and scrapers to compose an ensemble pattern that rests on a kata foundation. Musicians also blow the vaksin, a set of bamboo trumpets of various size and pitch. The characteristic augmented fourth of the vaksin scale clashes with the tonality of the songs and lends Rara music a feeling of dissonant polytonality. This penchant for clashing dissonance comes through not only in music but also in brilliant, sequined, multicolored costumes, and in the juxtaposition of vulgarity, politics, and religiosity in song texts. The vaksin circulate melodic motifs in hocket style that recall some vocal styles of Central Africa.

"M'pap mache a tè anye" (circa 1992) by Rara La Bel Fraicheur de l’Anglade (extract).

Rara music enlivens chay o pye (french : charge au pied; english, weight on the foot) and rabòdaj, dances that call for fancy footwork and a shimmer of the shoulders to show off the flash of costume elements. A majè jon (french : majeur jonc; english : baton major) decked in the most brilliant of costumes twirls his baton and manipulates magic with his feet. Dances borrowed from Carnival (maskawon) and Vodou (kongo) round out the Rara repertory.

A group of peasants pass through the provincial town of Ville Bonheur. They have adopted the dress and accessories of their patron lwa, Kouzen Zaka, especially the straw hat and satchel, denim clothes, rattle, and calabash begging bowl. The rattle accompanies their singing.

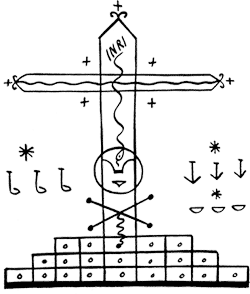

Vèvè for Gede.

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. Backdrop

2. The musicians of Vodou

3. The Guinea room

4. The Kongo/Petwo room

5. Work and celebrate: konbit, carnival, and rara

6. Vodou music in neo-traditional contexts: folklore and roots music

Bibliography / Discography

Musical examples

______________________________________

by Dr Lois Wilcken

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Général de la Guadeloupe, 2005