Laméca file

Afro-Colombian music

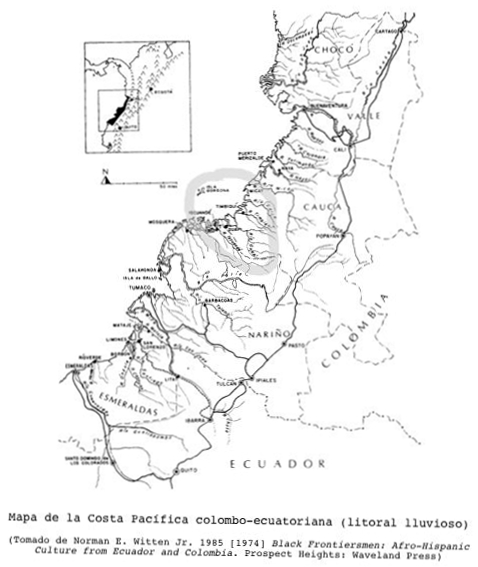

2. THE SOUTHERN PACIFIC

The southern Pacific coast of Colombia, stretching into Esmeraldas province in Ecuador, is, like the Chocó, an isolated rainforest region where some 90% of the total population is descended from the enslaved Africans brought in chains for the labor of gold mining. The 5% of the population that is indigenous lives largely in their own villages, far upstream, and a smattering of settlers from outside the region lives in the region’s larger cities.

Yurumanguí river (2006).

Photo : Michael Birenbaum Quintero

Rivers

Most human settlement in the southern Pacific is along the many streams and rivers that flow westward from the mountains that separate the region from the rest of the country into the ocean. The rivers provide the major arteries of transportation and the hubs of human settlement in the area. People take advantage of the downstream tide to row their canoes downstream to the plots, a few minutes hike into the jungle, where they have crops to gather. In the downstream communities, women head to the ocean-front swamps to dig for mollusks and men head out to the sea before dawn to fish, a candle and a cooking pot burning in the prow of their canoes. They return at the noontime upstream tide.

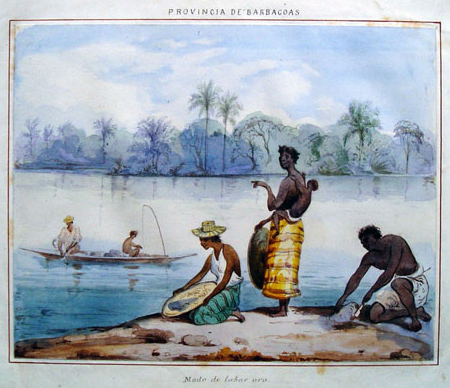

"Washing Gold” (Barbacoas Province).

Aquarelle de Manuel María Paz (1851)

In the midstream communities, as this tide washes away dirty water, women assemble at the shoreline to wash their laundry in the fresh water and gossip, as children swim and fill plastic receptacles with the day’s drinking water and men descend to the river with bars of blue laundry soap on sticks for a bath.

During the rainy months, the upstream communities build sluices and runoffs to pan the riverbed for gold, as they have since their ancestors were brought to the region in the seventeenth century.

Harsh life

Life in the Pacific coast can be rough. The work of fishing, farming, and mining is arduous. There are poisonous snakes, vampire bats, gastrointestinal parasites and numerous tropical diseases. Health coverage, aside from traditional herbalism, is minimal.

Electricity and telephone coverage are fairly new in the region, and still sporadic or nonexistent in some areas. Connections with the interior, along two two-lane “highways,” are often blocked by landslides, although there is air service to some towns for those who can afford it. Otherwise all transport is by river and sea routes, subject to the moods of the sea and the occasional attacks of pirates. By the end of 1990s, with the arrival of guerrilla groups, drug traffickers, and other armed actors in many parts of the area, the region has been immersed in political and criminal violence.

Juntas de Yurumanguí (2006).

Photo : Michael Birenbaum Quintero

Displacement from their land, and ruptures with traditional cultural forms has accompanied the arrival of these actors and of large agroindustrial concerns. Underpaid temporary work in the larger towns and villages or in cities of the interior has often replaced subsistence agriculture and traditional fishing and mining.

Resistance and résilience

It is in this context of resisting and adapting to the harsh but abundant environment, the depredations of outsiders, the lack of services or infrastructure, and other difficulties old and new, that the black inhabitants of the southern Pacific have forged an entirely unique set of cultural, musical, and religious traditions.

The resilience and creativity of southern Pacific Afro-Colombian culture is particularly manifest in the region’s musical traditions. Marimba and traditional singing was designated Intangible Cultural heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2010 (more informations here).

Marimba music and traditional chants from Colombia's South Pacific region (by UNESCO)

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. Black Colombia

2. The Southern Pacific

3. Currulao, the marimba dance

4. Arrullo, a lullaby for the Saints

5. Alabados and Chigualo, music for the dead

6. Black Pacific modernities

Musical illustrations

Sources

______________________________________

by Dr Michael Birenbaum Quintero

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Général de la Guadeloupe, 2009-2016