SUMMARY

1- A Panorama of Dominican Folk Religion and its Music

2- Afro-Dominican Religious Brotherhoods and their Palos Music

3- Case Study of an Afro-Dominican Cofradía: The Brotherhood of St. John the Baptist of Baní and its "Sarandunga"

4- The Dominican Saint's Festival and its Music

5- The Drum Dance [Baile de Palos]

6- Transnational Dominican Palos Music

Musical examples

Sources

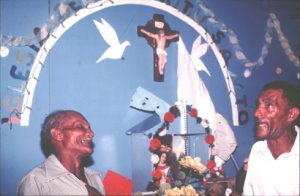

Audio 1 - “Salve de la Virgen" (M. E. Davis, 1973) Apart from the rosary, the Salve Regina prayer, sung in Spanish to an infinite number of musical settings, is the indispensable musical genre of the saint’s festival throughout all regions of the country. It is a Marian antiphon which antedates the eleventh century. In Spanish, the prayer begins as follows : Dios te salve, Reina y Madre de Misericordia; This prayer is now officially in disuse by the Church, but was an important aspect of devotion by the first colonists. It is said that when land was sited, Columbus's sailors fell to their knees on deck and sung a Salve Regina. Thus we can see that the conservative nature of religious ritual preserves archaic practices in the living oral tradition. A saint's festival is held traditionally from 6:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. on the eve of the saint's day and sometimes throughout the day (interestingly similar to Jewish custom). The event begins with a "tercio" or "third," that is, third of a rosary, prayed before a special altar set up in the living room of the sponsor's house. This is always followed by three Salve Reginas or similarly sacred songs. The same is repeated at midnight and then again just before dawn. In certain more Hispanic areas of the country, theSalves continue throughout the night until the next tercio. Outside there may be social dance, and, on the periphery of the grounds, a spontaneous competition of décimas (improvised poetry recited in competition), stories, and riddles, as well as games of chance (juegos de azar). In the more African-influenced areas or enclaves, the palos long-drums are also part of the saints' festivals. In such cases, three sacred palos pieces follow the tercio and the three sacred Salve Reginas, and then any pieces may be played until the next tercio. In the East, Salves are sung in the altar and palos are played outside in a rooved patio, the enramada; whereas in the Southwest, they may be interspersed with palos in the folk chapel, that is, separated temporally rather than spatially.  The creole, non-liturgical "Salve con versos".  The creole, non-liturgical "Salve con panderos" (more Africanized than the "Salve con versos"); pictured : a pandero and a mongó drum (held between the knees). Although the Salve Regina, including some archaic musical settings, has been retained, it has also evolved into a creole genre in many regions. Thus, the Dominican Salve is comprised of two coexisting subgenres: the sacred, liturgical Salve, called "Salve de la Virgen", and a less sacred, non-liturgical Salve with regionally-varying forms of accompaniment. The former is antiphonal or responsorial, melismatic, sung in a high, tense voice, and has no instrumental accompaniment. The latter is in the characteristically African-derived structure of call-and-response, is sung lower in the register and with a more relaxed voice, and is accompanied polyrhythmically by instruments which range from hand-clapping to a proliferation of hand drums (panderos) and small drums to even the palos long drums. The sacred text is lost in this Salve variant, and what remains of its sacred character is its performance before the altar. The saint's festival is not a context for spirit possession, except by the occasional appearance of the spirit of a former sponsor. However, if the sponsor is a vodú / spiritist medium, then spirit possession does occur by vodú deities [see chapter 4]. A second main religious musical context associated with the saints is that of procession and pilgrimage. Both entail walking in procession, but the procession is local and starts and ends at the same place, a church or folk chapel, whereas the pilgrimage is regional and starts in many places from which people converge on the pilgrimage center, then disperse in unorganized fashion. The most renowned pilgrimage sites in the country are to the Virgen de Las Mercedes (Our Lady of Mercy), the national patroness at the Santo Cerro in La Vega (northern region), (September 24), and to the beloved Virgen de la Altagracia, the “national protector,” in Higüey, Altagracia Province (eastern region) (January 21 and August 16). A third important pilgrimage center is to the Santo Cristo de los Milagros (Holy Christ of the Miracles) in Bayaguana, Province of Monte Plata (central-south region). The most ancient pilgrimage, probably pre-Columbian, is to St. Francis of Assisi at the cave in Bánica (central southwestern border area). This same interior southwest region gave rise to the greatest messianic leader and folk-healer in the country's history, Liborio Mateo (killed in 1922); as pilgrimages are directed to deities in payment of vows for healing, they were also directed to him in search of healing. Audio 2 - "Tonada de toros" (M. E. Davis, 1976) The East has special Church-administered brotherhoods associated with the devotion and pilgrimages to the Altagracia or Santo Cristo. In their rituals for collection of alms and donations of bull calves, they sing improvised, unaccompanied musical conversations called "bull songs" (cantinas de toros) of obvious Hispanic origin. The nightly stops on their routes to the pilgrimage centers are in effect saint's festivals; and in these cases, the "bull songs" are another musical genre performed, as they are at the death rituals of one of the brotherhood members.  The congos drums of the cofradía (brotherhood) of the Holy Spirit in Villa Mella play at the túmulo (symbolic coffin with altar) in the final novena for the dead. Death rituals are the final main folk-religious context of musical performance. Rituals may occur at various points in the death and mourning cycle: at the wake, in the procession to the cemetery and the return, during the nine-night novena, during the finalnovena, or on the anniversary of death. The specific rituals emphasized and their musical content depend on the region of the country and whether or not the deceased was a brotherhood member. All death rituals are based on the rosary which, in some areas, may be partially sung. For members of Afro-Dominican cofradías, and others who request them, the palos are played. For children - considered "angelitos," little angels, free from sin - there are traditionally special wakes called "baquiní" with their special music. The "mediatuna" is a common genre from the Cibao (northern) region, and there may be certain songs for the burial procession by the entourage of one's little friends, en route to and returning from the cemetery. Audio 3 - "Angelito, vete" (M. E. Davis, 1973) The growing Haitian presence in the Dominican Republic is expanding and influencing the genres of folk religion and music. Haitian vodoun is prominent in the bateyes or sugar-cane communities, as is gagá, a Dominican pronunciation of rará, a Lenten type of society which is carnavalesque for the public but as deep as vodoun within.

By Dr Martha Ellen Davis |