SUMMARY

1- A Panorama of Dominican Folk Religion and its Music

2- Afro-Dominican Religious Brotherhoods and their Palos Music

3- Case Study of an Afro-Dominican Cofradía: The Brotherhood of St. John the Baptist of Baní and its "Sarandunga"

4- The Dominican Saint's Festival and its Music

5- The Drum Dance [Baile de Palos]

6- Transnational Dominican Palos Music

Musical examples

Sources

4. The Dominican Saint's Festival and its Music

Altar of saint's festival: For the cofradía of Santa Rita in the town of San Juan de la Maguana.

The Dominican saint’s festival or “velación” is the most common event in Dominican folk Catholicism and musically the most diverse. (The velación is alternatively called “noche de vela,” “velada,” or “velorio de santo,” depending on the region.) It may be sponsored by an individual or an Afro-Dominican religious brotherhood (cofradía) and is held at the family homestead or the folk chapel of the brotherhood. Velaciones of individual sponsorship are offered in payment of a vow (promesa), a contract with a saint for divine healing; traditionally, once offered, they become annually recurring and inherited. Those sponsored by cofradíascelebrate the brotherhood’s patron saint, or a velación may be offered by a member of the brotherhood as a vow.

"Throne" for royalty, accompanied by Salves en route to annual family saint's festival of Sixto Miniel, "capitán" (master drummer) of the cofradía of the Holy Spirit, Villa Mella.

The social organization of a brotherhood’s annual saint’s festival is replicated in those of individual sponsorship, which assume the structure of a brotherhood in miniature, activated once a year. This is particularly true in the Central-Eastern area, where the larger cofradías are no longer found. In that region, the velación leadership includes a “king” and “queen”-for-a-day, viceroy and "vice-queen," who enter the homestead grounds in procession, singing and playing Salves and bearing a specially-made arch (arco or trono "throne") held above the dignitaries, decorated with tissue-paper flowers. The king serves as the authority figures for the domain of the palos dance in the enramada or rooved patio, and the queen officiates and contributes to the Salveperformance at the specially-prepared altar in the living room, above which the arch is ceremoniously placed upon the entry of the regal delegation.

Salves con panderos. Grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Sixto Miniel perform Salves at the annual family saint's festival. Instruments pictured: panderos (more commonly a woman's instrument).

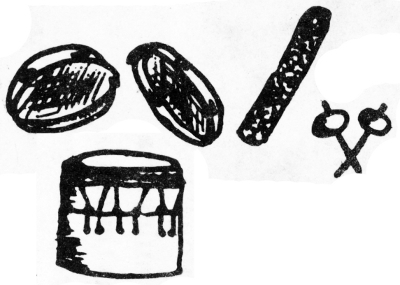

Salves instrumental ensemble of the central-south and east. Panderos (hand drums with a few jingles), typically women's instruments, of which there can be an infinite number in the ensemble; mongó (a single small drum held between the knees of a seated male player); güira (metal scraper); and a pair of maracas (shakers).

In the velaciones, different genres of music are assigned to different placement temporally in the ritual procedure before the altar or spatially in the house or grounds, and that these vary regionally. The Salves are always performed at the altar specially prepared for the event. The palos drums, when used, may be played during certain periods near the altar (as in the southwest) or outside in the enramada (as in the east).

The ritual procedure entails three tercios, or thirds of a rosary, at 6:00 p.m. to begin, at midnight, and just before dawn. Each is followed by three sung sacred Salve Regina prayers (in Spanish), which are rendered in antiphonal or responsorial structure and are melismatic, unmetered, and unaccompanied. These are followed, in the south, with three sacred drum pieces.

In between these ritual temporal markers, the music is unspecified and varies regionally. In some areas, such as the southwest, the music entails additional Salve Reginas until the next tercio. This seems to be the most traditional type of velación, and it appears that the palos were formerly much less widely diffused in the country than they are today. For example, according to oral history, the palos did not spread south of the Neiba Mountains from the San Juan Valley (interior southwest region) until some forty years ago; and then it was the Salves con palos associated with spirit possession (discussed below) which diffused south rather than the sacred Palos del Espíritu Santo associated with the cofradía of the Holy Spirit.

Audio 1 - "Salve con panderos" (M. E. Davis, 1973)

Salve con panderos, a creole-style Salve accompanied by hand drums. The secular text praises the public-works projects of then president Joaquín Balaguer (Monte Plata).

In this region, the Salve between the tercios is sung largely by men competitively (en desafío) like the sung improvised conversations elsewhere of Mediterranean influence; the palos, if any, are interspersed or played outside. In the eastern region, the tercios are interspersed with an Africanized, that is, creole type of Salve, characterized by the loss of all or most of the sacred text, an African-derived call-and-response structure, polyrhythmic accompaniment by handclapping or small membranophones. In the east, the palos for dancing played outside in a rooved patio (enramada).

Audio 2 - "Salve de la Virgen" (M. E. Davis, 1973)

Salve de la Virgen, at a nightly stop en route to the pilgrimage center of Higüey (East) by a hoarse pilgrim who exhorts others to join her singing at the altar. (Santa Lucía, El Seybo).

When a velación is a nightly stopping point on a pilgrimage route in the eastern region--to the Virgen de la Altagracia in Higüey or el Santo Cristo de los Milagros in Bayaguana, and other secondary pilgrimage sites—another musical genre is added to the multifaceted saint’s festival. In this old cattle region since the earliest colonial times, a type of Church-managed brotherhood (of a very different sort than the cofradía) is superimposed upon the pilgrimage routes, namely the so-called “tonada de toros” (bull songs) in reference to the donation of bull calves to the Church, rounded up by the brotherhood members prior to the pilgrimage. The tonada de toros, performed seated around a table in a special location, is a sung improvised conversation, another heir of this sort of Mediterranean musical phenomenon, in this case perhaps derived directly from the Canary Islands.

Another element, albeit not musical, is added to the saint’s festival if the sponsor is a vodú medium (servidor, servidora): the element of spirit possession by deities (“misterios”), saints with African or creole counterparts. In this case, following the prayed “tercio” and the three obligatory Salves de la Virgen, non-liturgical Salves will invoke spirit possession by vodú deities. If not of vodú-medium sponsorship, the only possession that may occur is by a former sponsor to enjoy the fiesta or reprimand his/her heirs for the lack of attentions of food and drink to the drummers.

Salves con palos, as played at a saint's festival sponsored by a vodú medium, southwestern region.

Audio 3 - "'Guaracha' de Liborio" (Miguel Fernández, 2002)

Salve con palos "'Guaracha' de Liborio" in honor of Liborio Mateo, the greatest messianic leader in the country's history (d. 1922) (San Juan de la Maguana - interior southwest).

For a saint’s festival with spirit possession, the instrumental ensemble for the non-liturgical Salves may be either the ensemble of small hand- and other drums or the palos long drums. (Note: Such a case of “Salves con palos” should not be confused with “palos” music per se, which refers only to the semi-sacred music traditionally associated with cofradías.) Unlike the more African counterparts in the Americas, this creole music does not vary in rhythm with each deity; rather, the variation is in melody and text only.

This type of saint’s festival is on the rise and proliferating, as are other vodú devotional or celebratory events (called "horas santas" and “maní” or “priyé”). In accordance with the diffusion of the formerly censored Dominican vodú, it is the “Salve con palos” which has extended into transnational Dominican communities particularly in New York City as a musical business venture to satisfy this ceremonial need [see chapter 6].

Dr. Martha Ellen Davis

Archivo General de la Nación (Dominican Republic) & University of Florida (USA)